How do you, as an entrepreneur, “think big” about a startup?

Start by reading the page on transcendental wealth as well as the page on the $1 billion startup.

Now you have to imagine/envision that investors will be funding your company in the same kind of way that investors funded Nest, or Dropcam, or Terra Bella. In other words, you have an idea that can support investment and you are going to lay out a 5-year plan to take in 3 or 4 rounds of funding.

This is how entrepreneurs think big, and conceive of big financial success. If you look on Crunchbase, you can find all kinds of companies following this path.

Terra Bella Example

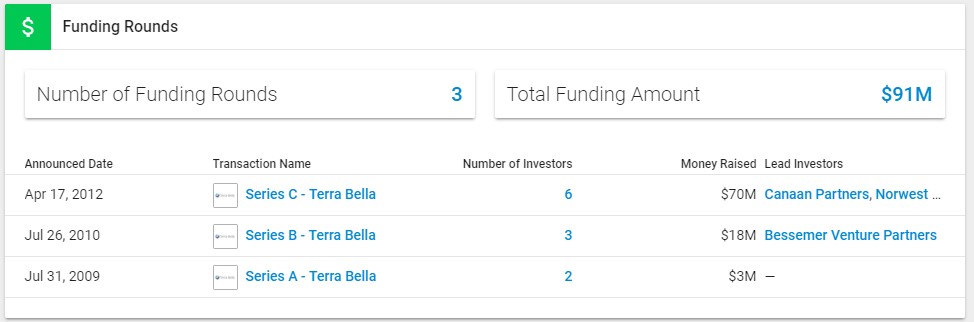

Terra Bella (originally Skybox) is a perfect example. If you find it on Crunchbase, you see this:

https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/skybox-imaging

Terra Bella took in $3 million, then $18 million, then $70 million. Why? Part of it has to do with dilution, part of it has to do with the company’s ability to “digest” or “utilize” money, and part of it has to do with building credibility. In other words, this company could not “digest” $70 million as a 3 or 4 person startup. Even if it tried too, there is no way that the company’s valuation could support the dilution that $70 million would cause. So the company took in $3 million, grew larger, de-risked some of its assumptions and hypotheses, gained credibility by delivering on some milestones, etc. Then the company was large enough to handle $18 million without terrible dilution. Same thing. Then it was large enough to take in $70 million (with this amount of money it can start launching stuff, and did so in November 2013). And then the pay-off: Google acquired the company for $500 million in 2014.

Terra Bella represents a perfectly executed investor-funded play. Learn more about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SkySat

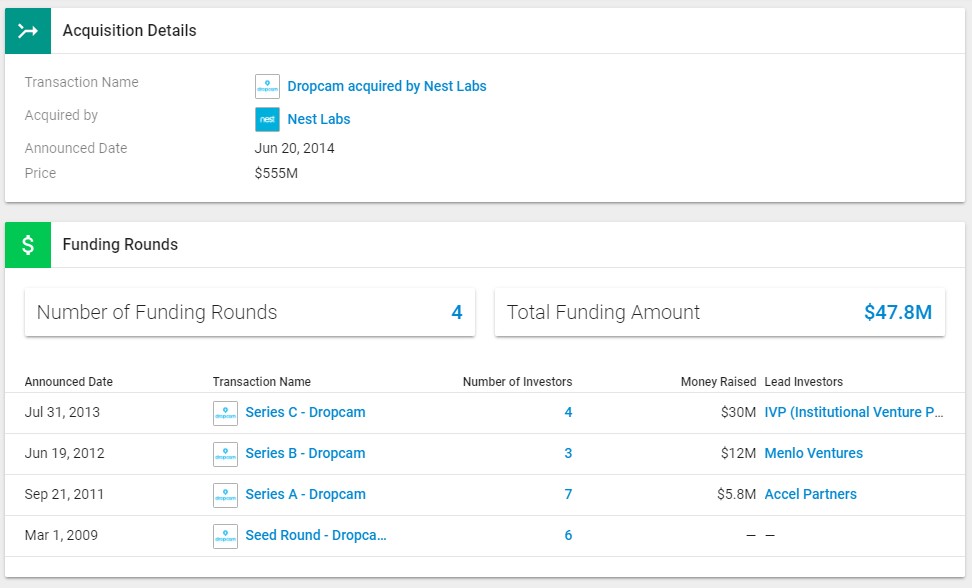

Dropcam Example

Dropcam unfolded in exactly the same way:

https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/dropcam

A seed round, three VC rounds, then acquired for $555 million.

Dor Technologies, as described on the $1 billion startup page, will follow the exact same path: https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/dor-technologies

Think through your startup

So now think about your own startup. Assume that you will be able to get started in an accelerator, then get $300,000 to $600,000 in funding from a seed-stage angel, then get a Series A round in the range of $3 million, and so on. And then your plan is to exit for $200 million or $500 million in an acquisition. Or maybe even do an IPO. This is how you think big as an entrepreneur in the current startup ecosystem in the United States.

Or, if you don’t want to think that big, think more in terms of a base hit, with an acquisition at $10 million, or $20 million, or $50 million, as described on the transcendental wealth page.

If you are going to ask investors for $X million in series A or B, how big is X? It depends on how you model things:

- Do you need a sales force? How much will that cost?

- Or is it more of a retail play? How much will that cost?

- How much will you spend on marketing? Why?

- What will your staff look like, and how will staff grow over time? How much money will you need to have on hand to pay them prior to becoming profitable?

- When will you reach profitability?

- What will your sales look like over time? Why?

You create a financial model to answer questions like these, and many others. If you plug into Google and do some searches, it is easy to find spreadsheet templates that will help you model just about any kind of company you can imagine:

As you are building a model like this, it is always best to tie things together rationally. So if in year 3 you think you will sell 300,000 of your widgets, why do you think that? If the answer is, “we believe our cost of customer acquisition is $25 per customer, and we are going to invest $7.5 million in marketing to hit that sales number,” then that is rational. It is cause and effect. But it also demands that you raise $7.5 million from investors, just for the ads. Then you need the kind of staff that can manage an ad budget like this. Then you also have to raise money to build the inventory, and you will need a warehouse to hold all of the inventory… Then… As you think these things through and start to model them out, it becomes obvious when you will need to take in money, and why.

Pitching to investors

Usually, around the same time as you build your financial model, you are also building your business plan and your investor pitch deck. Again, Google is your friend. There are all kinds of pitch deck templates and business plan templates online. If you have never done a pitch or seen a pitch to investors, here are some helpful resources to get you started:

- Sequoia Capital Pitch Deck Template

- David Rose’s TED talk on pitching to a venture capitalist

- TriFusion Devices’ pitch from the Rice Business Plan Competition 2016 held in Houston, TX

So in your model, plan and presentation, explain why you think your cost of customer acquisition is $25 (keep in mind that Nest might have spent $100 per unit in ads, endcaps, etc. to acquire each of its customers – this is one reason why the original Nest thermostat was priced at $250). Then you have to bake that cost of customer acquisition into the price of your product, along with all of the other costs. Eventually you will have an end-to-end, 5-year financial model that lays out your complete plan.

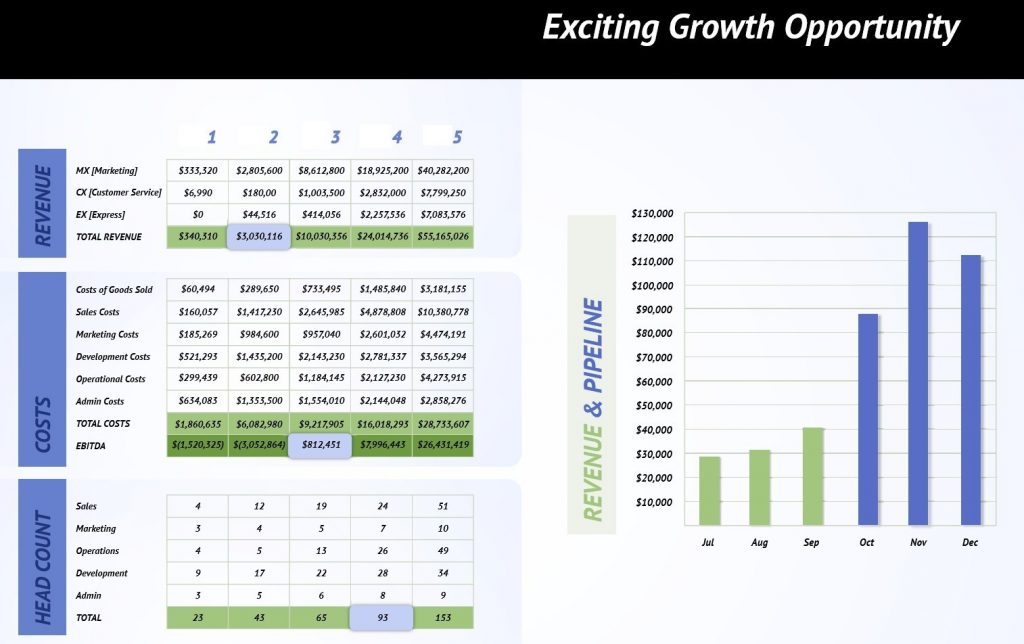

Above you can see a financial slide from a typical pitch deck (in that case for a SaaS company). This is the kind of slide that an entrepreneur would use to try to raise money from investors. The slide summarizes his/her financial projections over 5 years. Please print this slide out and look at it as a team – stare at it long and hard, and grok everything it is saying. This company was pitching to investors, and this is how they summarized their pro forma financials. The graph on the right shows their actual revenue for the last 3 months (green) and their projected revenue for the next 3 (blue) based on their present sales pipeline. The point of this is to show: a) they have traction now and b) they are seeing growth in sales even now, pre-investment. Then:

- The first table on the left shows their revenue from 3 different revenue streams.

- The next table is their costs. “Development costs” means software developers – this was a software as a service (SaaS) company. At the bottom is EBITDA. The first 2 numbers are in parentheses, meaning they are negative. These negative numbers show why the company needs investors. To do what they plan to do in year 1, they need $1.52 million to balance out the financial hole they are creating. They will need money again in year 2. Then they become cash flow positive in year 3. In year 3 they will likely raise money again in order to accelerate growth (rather than growing strictly out of revenue).

- The last table is head count. This is how they envision growing their staff over time in the different departments.

Where did they get all of these numbers? They built a financial model in a spreadsheet just like you are doing, and then they distilled this slide out of the spreadsheet. When you present to investors, a summary page like this would be a very good thing to have, alongside your full spreadsheet which you are happy to show people on request after the presentation.

Here are five other things to keep in mind:

- You have to think rationally about how you are going to sell your thing. Are you going to use a direct sales force? Trade shows? Radio ads? Web advertising? Outdoor advertising? Research what these kind of things really cost. For example, it might cost $15,000 to $25,000 to attend one “real” trade show (e.g. CES), even with a tiny booth. Why? You have to pay for the booth space, pay to furnish the booth space, pay for the travel expenses of 2 or 3 people, buy handouts and Tchotchkes, etc.

- You need a well-thought-out sales and advertising model when you talk to investors. If you come in and say, “well, we will have a web site, and we will get traffic from our friends on social media”, that is going to get you kicked out the door. Do some massive research, talk to experienced people, talk to advisers/mentors, etc.

- In your model, assume that all team members will be working for your company full time for the duration. How much salary do you pay yourselves? For the sake of this model, assume ~$40K per person per year in year 1, and then boost it some once you achieve break-even. Then add in other payroll costs. Assume $600/month for benefits per employee. Assume a 16% uptick for federal stuff (FICA/FUTA/SUTA/etc). Consider 4% 401(k) matching. [In a place like Silicon Valley, especially if you are hiring developers, the employee costs will be radically higher than this, like 5X higher. Again, research…]

- Now, over time, how and why are you going to add other employees. If you are going to need two scientists to do research, add them. If you plan a sales team with 5 people, add them, along with people to support the sales staff. Etc. Look at how they bring in employees in the slide above.

- You must create a reasonable price for your product. You cannot come into a meeting and say, “Well, our BOM is $60 and we are therefore going to sell it for $70.” It needs to be much more detailed, as in “Our BOM is $60, leading to a COGS of $110, and our wholesale price is $180, 20% of which is profit. This leads to a MSRP of $360.” This is the link for a $185 shirt: https://

elizabethsuzann.com/blogs/ stories/money-talk. Look at all of the overhead she is carrying – it is costing her $100 per shirt for her operating costs (which seems excessive by normal standards, but it is what it is in her case and she provides a lot of detail). And note that this is not a retail price – this is a direct sales price (essentially her wholesale price). If she wants to sell this shirt in Macy’s, the MSRP will probably need to double her $185 number.

Even if your plan is much more modest, like, “I plan to grow my little web dev company from me alone to 10 people and $1 million in revenue over the next three years without any outside investors,” it would be worth your time to spend a week laying out a financial spreadsheet and a real business plan, just to work through the details. And then, as you are doing that, I would probably ask you, “why not think bigger?”

Financial models are always guesses, based on assumptions. Especially early ones. Please make educated, thoughtful assumptions based on research. Google is your friend – ask Google lots of questions. Be able to support all of your numbers with research and advice from real players when you build a financial model.

And then go execute it.